Will the Renters’ Rights Act make any difference?

Weak enforcement has always been a feature of England's private rented sector. Will the latest of many previous attempts at legislating change actually be effective this time?

Here, Tom Entwistle explores the issues and looks at the potential for real change.

The Renters’ Rights Act gives councils stronger investigatory powers. But with enforcement teams hollowed out, prosecution rates tiny and the rogue-landlord registry near-empty, will this new set of comprehensive legislation, in the government’s own words, “The biggest change in the PRS for a generation, change tenants’ lived reality — or will it merely rearrange the deckchairs?

The new Act promises sweeping new powers, but do councils have the resources to use them? Stronger powers matter, but only if resource capacity, funding and political will follow. Local authorities and the court system are both under-resourced and overloaded, what chance for real change by routing out the rogues and criminals?

The tenant issues

Imagine the scenario: a young family in inner-city Birmingham. They contact their local council about persistent damp and a broken boiler. The landlord promises to fix it for the umpteenth time. Weeks go by with no progress. No follow-up inspection arrives from the council. Their complaint has disappeared into an intray with a backlog with others, while the landlord quietly re-lets the property once they move out.

This scenario is depressingly common across England. Under the new Renters’ Rights Act 2025, due to come fully into effect in May next year, councils will acquire enhanced powers to investigate, inspect, and penalise rogue landlords like this one. On paper, the overhaul promises a major shift in a tenant’s power to get things done, will it transfer to practise?

The scale of the problem today

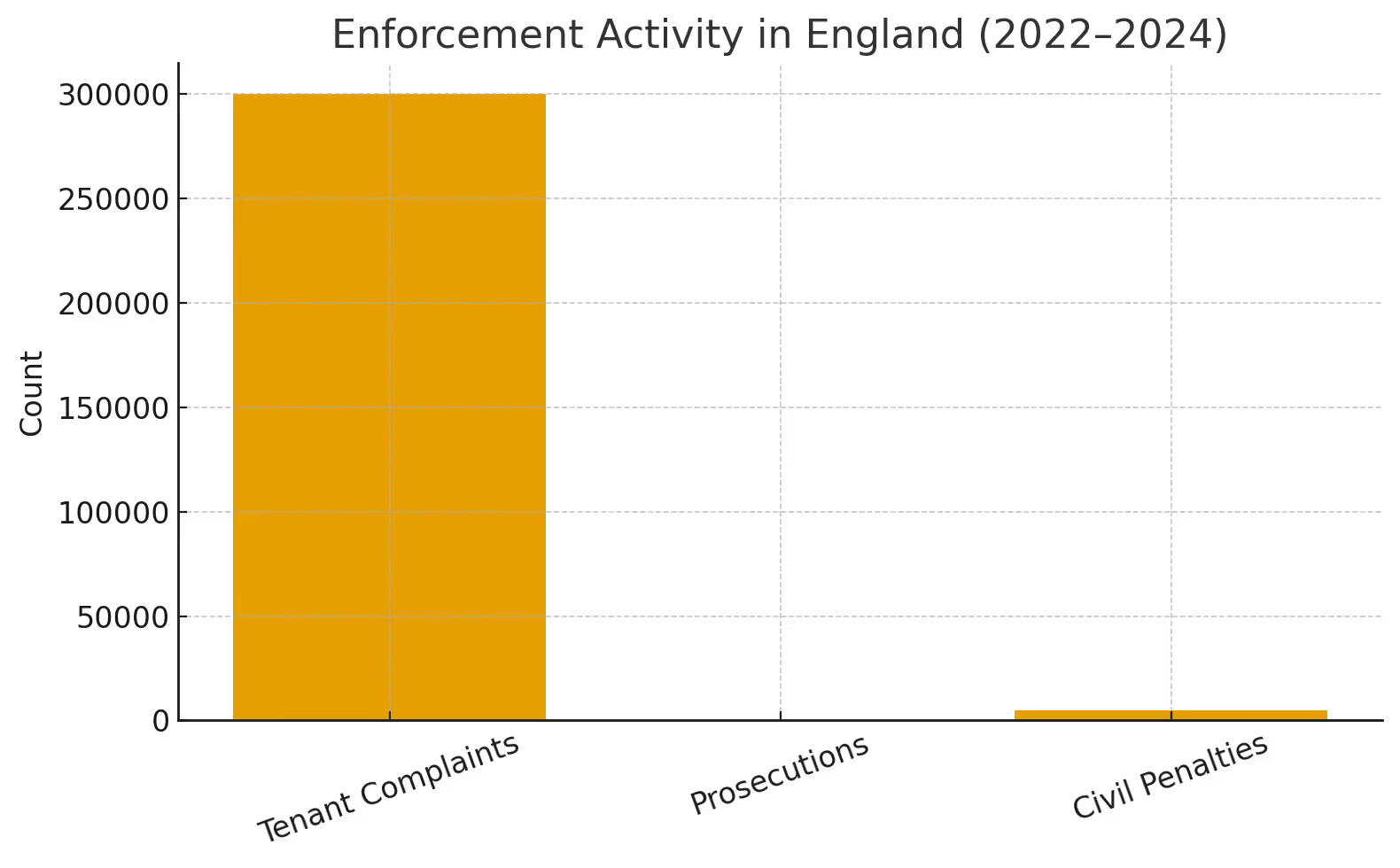

According to recent data, across England’s local authorities, between 2022–2024 nearly 300,000 tenant complaints were logged, yet research shows that only 640 landlords were prosecuted and just 4,702 civil penalty notices were issued. According to The Guardian, this represents under 2 per cent of complaints resulting in any formal enforcement.

What’s worse, two-thirds of councils did not prosecute a single landlord in that period. These numbers reflect findings from earlier research. A five-year survey by public-interest lawyers showed more than 100 councils had not brought any landlord cases to court from 2019/20 to 2023/24, even though the overall number of complaints reached hundreds of thousands.

When councils did issue civil penalties or fines, they often struggled to collect them. One analysis carried out by the National Residential Landlords Association (NRLA) found that less than half of fines levied between 2021–2023 were ever recovered.

From a tenant’s perspective numerous reports are ignored, landlords often avoid the full consequences, councils either lack the ability or the will to take stronger action and if cases do go to court, fines are often meagre.

Why is enforcement so weak?

Budget cuts and staffing collapse. Local authority housing enforcement teams have been hollowed out over the last decade. With severe cuts to council funding, few authorities can spare the officers, or the legal support and inspection capacity needed to investigate and prosecute complex landlord offences. Several councils responding to Freedom of Information (FOI) requests admitted they had issued few or in many cases, no penalties, despite receiving substantial complaint volumes.

Despite very adequate existing legal powers provided under current legislation, such as the Housing and Planning Act 2016 and many more, councils rarely issue civil penalties or pursue prosecutions. In many locations, there’s only a handful of officers available to handle cases. One review found that just 20 local authorities accounted for 77% of all successful prosecutions in a three-year period.

This concentration underlines the realities, a minority of councils have the capacity and will, the majority do not. And where penalties are issued, councils often struggle to collect the fines which undermines their enforcement budgets and the credibility of deterrents.

It’s in every responsible landlord’s interest that the rogues and the criminals operating in the PRS are given real deterrents but all the available evidence shows that this is not happening.

To be fair to all local authorities, building a case strong enough for prosecution requires tremendous amounts of resources: human resources, time, evidence-gathering, inspections, court delays and follow-up. Housing standards, despite standardised tests – HHSRS, and the tenant-rights laws, are labyrinthine.

Councils in consequence often prioritise their statutory duties (homelessness) over proactive enforcement against rogue landlords. The research into the issue consistently reveals that enforcement is often reactive, complaint-driven, and treated as low priority.

What the Renters’ Rights Act promises — in theory

The Act brings a whole suite of major reforms, including the abolition of no-fault evictions, fairer rent reviews and limiting upfront rent payments.

For enforcement of property standards and landlord behaviour promises to be stronger than ever before, councils will gain greater investigatory and entry powers, expanded grounds to issue higher civil-penalties, and stronger obligations to act rather than rely on informal warnings.

Under the updated guidance, there will be no prescribed requirement that councils must first issue warning letters, they will have the power to jump straight to inspection and formal enforcement. A new private-rented-sector database plus a landlords / agents’ ombudsman service will also become available soon.

Taking these additional powers together, and if effectively applied, the changes could — in theory — close many of these long-standing loopholes referred to above, and make it a lot harder for rogue and criminal landlords to hide in plain sight.

Given this, can the new legislation fix the problem?

The new Act does significantly tighten the legal framework. Investigatory powers, the ability to impose higher penalties, and the obligation for landlords to act formally (rather than rely on informal warnings) are important steps forward. If implemented properly, these powers have the potential to reduce the informational and legal obstacles that allow some rogue and criminal landlords to squeeze through the gaps and operate with impunity.

But legislation alone will not solve the core problem, it will take real capacity enhancement and political will to make a difference. How high a priority will this issue rise within councils’ administration systems? When money is so tight, when many are on the verge of bankruptcy, and real threats of staff redundancies dominate people’s thinking?

Real change requires sustained investment, adequate staffing, national coordination, and political pressure. A fine or criminal penalty is only an effective deterrent if it is substantial (painful), there is a reasonable likelihood of being caught, and collection is carried out. Currently, the chances of all that are slim and will stay that way unless enforcement efforts are substantially strengthened.

If councils continue to struggle with funding and collections, the Act could end up being yet another symbolic measure that makes the lawmakers in Parliament feel better, but is just another veneer of reform that leaves the worst offenders untouched.

The new obligations (database, ombudsman, etc.) will result in higher costs for landlords, which inevitably will be passed on to tenants, and their implementation may also face long delays due to persistent resource limitations. Without dedicated budgets, ring-fenced enforcement funds, and an overhaul of how councils prioritise housing enforcement, the Act could still amount to little more than changes on paper.

What measures must councils take to turn the Act into real protection?

They should be ring-fencing and reinvesting fines and penalty charge notice revenue to fund permanent enforcement teams, giving councils a sustainable enforcement budget rather than relying on dwindling general funds. Legal costs and complexity often deter councils from pursuing cases, so pooling resources regionally could help lower the cost-barrier for prosecution.

Councils need to identify landlords with criminal convictions, log them in the national database, and oversee or prohibit their properties from letting, making sure they cannot rent under a new identity. Councils should publish enforcement activity, conviction and penalty rates locally, as well as regularly updating the rogue-landlord database listings.

Proactive inspection programmes will increase the quality and frequency of genuine complaints, will improve evidence collection, and give tenants real leverage, while multi-agency, cross-council, possibly regional pooling of expertise. These kinds of legal and investigative resources will enable sustained action against serial rogue and criminal landlords.

In summary

If these reforms are properly enforced, they could improve the renting experience for those tenants who end up dealing with rogue or criminal landlords. A system where complaints currently go largely ignored has the potential to be transformed into one giving tenants rights with teeth, and no longer could landlords break rules with total impunity.

For responsible landlords, effective change could restore reputational trust in renting, marginalise the rogues who tarnish it, and remove unfair competition. A more regulated and enforced sector will benefit tenants and good landlords.

But as things stand right now, councils must commit to rebuilding their resources in this area before enforcement can be effective. The Renters’ Rights Act promises to hand councils the tools they need to crack down on rogue and criminal landlords, and at last begin to tip the legal balance toward fairness in the PRS for tenants and good landlords.

Too many councils are forced into inactivity in the PRS through budget cuts, staff shortages, political neglect, or weak incentives. This must change. This new legislation asks a great deal of responsible landlords to fully comply with all its measures. This will be all for nought if councils do not likewise respond.

.avif)

.avif)

Comments