Leasehold Reform in England: Where are we at, what’s changing?

Why does leasehold reform matter to landlords?

After years of political wrangling and promises, consultations and half-measures in legislation, leasehold reform in England finally got some commitment, moving from rhetoric into statute.

The Leasehold and Freehold Reform Act 2024 was passed into law under the Tory government, and now a major legal challenge to it has failed.

Labour ministers are signalling that this Act is merely the first stage of reform in its plans for a longer journey — one that could ultimately see leasehold replaced altogether by commonhold. But such radical change won’t come easily.

That ambition is radical given the powerful interested parties involved and the likely cost to them. In practice, reform will be messy, expensive and slow. For landlords, investors and managing agents, this is not a moral debate but a commercial and legal reality, one which raises some important questions: what has actually changed, what has not, and where does the risk now lie?

What Is Leasehold and why is it so politically toxic?

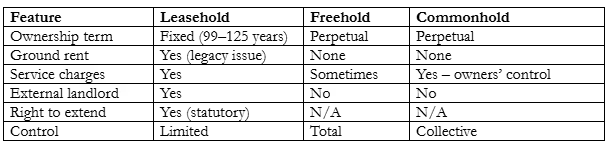

Under the English leasehold system, a buyer owns the right to occupy a property for a fixed period — commonly 99 or 125 years — while a freeholder retains ownership of the land and ultimate control of the building.

Leaseholders typically pay:

- An annual ground rent to the freeholder

- Service charges for maintenance

- Management by a managing agent

- Major works contributions, often unpredictable and substantial

Unlike freehold ownership, leaseholders do not own the building outright and have limited control over how it is managed.

The contrast with alternative tenures is stark:

This structure has fuelled decades of anguish and criticism by leaseholders. Ground rents became financial assets to owners, liabilities for occupiers. Service charges are often opaque and sometimes excessive.

Lease extensions became expensive once the lease terms dropped below 80 years due to marriage value*. Pressure on politicians has resulted in successive reforms, but root and branch reform has so far been avoided due to the high costs involved.

*Marriage value is the increase in the value of the property following a lease extension, and reflects the additional market value of the longer lease. The legislation requires that this increase in values or “profit” be shared equally 50/50 between landlord and tenant.

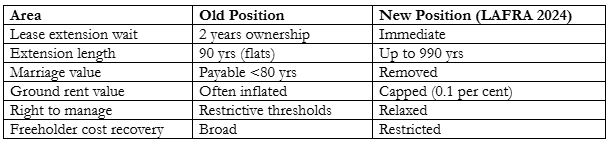

The Leasehold and Freehold Reform Act 2024 (LAFRA) is the latest in a line of reform Acts and represents the most substantial recalibration of leaseholder rights in a generation. It does not go as far as abolishing leasehold, but it does significantly weaken the economic mchanism that made leaseholds profitable for freeholders.

Here is the position after the 2024 Act:

The removal of marriage value alone is a seismic shift. For decades it inflated premiums payable by leaseholders once a lease lapsed below 80 years. Its abolition directly attacks a core source of freeholder value which is a source of major concern to the likes of private landlords, pension funds and insurance companies, owners of large swaths of leaseholds in the capital.

Likewise, the ground rent cap for valuation purposes curtails the ability to capitalise income streams that, in many cases, had little connection to the actual cost of managing a building.

Crucially, however, most of these reforms are not yet operational. They require secondary legislation, consultation on valuation detail, and implementation timetables that remain opaque.

Freeholders went to court over these measures

The 2024 Act’s passage was immediately followed by a legal challenge from freeholders and investment interests, arguing that the 2024 LAFRA unlawfully interfered with their property rights under Article 1 of Protocol 1 of the European Convention on Human Rights.

In October 2025, the High Court dismissed the challenge in full.

The judicial review brought by the freeholders challenged the abolition of marriage value, the cap on ground rent and the burden of costs for the freeholder in enfranchisement and lease extension cases.

Six freeholder claimants included Alpha Real Capital LLP, the Duke of Westminster’s Cadogan Group Ltd, Abacus Land and some other major freeholders. Together these owners control nearly 400,000 leasehold properties. Their main argument relied on Article 1 of the First Protocol (A1P1) to the European Convention of Human Rights, which protects the right to peaceful enjoyment of private property.

The High Court ruled that the new law was not “incompatible” with the ECHR and therefore dismissed their claim.

The court accepted Parliament’s right to rebalance the leasehold system in the public interest and found the reforms proportionate. This ruling matters because it removes a major legal roadblock to the implementation of the Act.

But with influential stakeholders involved and the value they could potentially lose, possibly running to billions of pounds, the ruling does not eliminate risk. Appeals still remain possible, and further litigation around the mechanics of valuation is likely once secondary legislation is published.

Leasehold reform has been ongoing incrementally for years

Here is the timeline of reform:

- 2002 — Commonhold introduced (but with minimal uptake)

- 2017–2019 — Ground rent scandal and consultations

- 2022 — New leasehold single home houses effectively banned

- 2024 — LAFRA receives Royal Assent

- 2025 — High Court challenge dismissed

- 2025–26 — Secondary legislation and a Commonhold Bill is expected

Changes to property rights change slowly and cautiously because the stakes are so high, mistakes are expensive.

Beyond Reform: The push to abolish leasehold altogether

The government’s longer-term ambition is explicit: no new leasehold flats, replaced by a reinvigorated commonhold system.

Under commonhold, flat owners own their units outright and collectively manage the building. No ground rent. No external landlord. No wasting assets.

On paper, it solves many leasehold problems. In practice, Commonhold has failed to gain traction since its inclusion in the 2002 Act.

Traditional English property rights stem from antiquity. The foundation of English land law is the feudal principle that all land is held, directly or indirectly, from the Crown. Individuals own not the land itself, but an "estate" in land, which grants them rights for a specific period. The primary estates in modern law (since the Law of Property Act 1925) are:

Freehold - “Fee Simple Absolute in Possession” - is the closest to absolute ownership, an estate of potentially unlimited duration, and is the most common form of home ownership.

Leasehold – a Term of Years Absolute - is an interest in land for a defined, fixed period of time (e.g., 99 years, or even a short-term tenancy).

There are barriers to a transition to commonhold

It is legally complex and difficult to structure in mixed use blocks. There are difficulties with mortgages creating financial uncertainty. Developers lose incentives because leaseholds are more profitable to them, and there’s no easy way to convert the existing leaseholds to commonhold.

The new government’s White Paper promises to tackle these issues, but the legislative detail has not yet been thrashed out. Until that happens, moving to Commonhold will remain an aspiration rather than a fact.

The cost – a question no one wants to think about

For a Labour government, abolishing leasehold is politically highly attractive but funding it when the government’s coffers are already under strain, is not.

Ground rents and enfranchisement values sit on institutional balance sheets. Pension funds and insurers stand to lose billions. What’s more, the prospect of retrospective law, interference with traditional legal rights, raises uncomfortable questions about compensation, legal certainty and investor confidence.

Recent press stories estimate that full abolition with compensation could run into billions. If the government tries to do this without compensation, not only is litigation from powerful stakeholders inevitable; the message it sends out to foreign investors, that English law is changeable retrospectively, destroys confidence in the system.

That in a nutshell is the central tension in leasehold reform, making the system fairer to leaseholders versus the economic reality – a cost running to billions.

Who benefits, who loses?

For the leaseholder, they will get longer leases, lower premiums and more control, but these will take time to materialise.

Conversely, for landlords and freeholders the traditional income streams will be eroded. Valuations will price-in political and regulatory risk, not just the lease length. For investors leasehold would no longer mean a static asset class. Now, with reforms hanging over them, landlords and freeholders’ assumptions about exit values, and their exposure to enfranchisement and reform risk, all matters more than they did a few years ago.

Conclusions

Leasehold reform in England is no longer an abstract theory, the government has said it is committed to root and branch reform. The law has already changed, and the courts have upheld it, but further reform is coming.

To change a system that’s been there for 1,000 years, to suit everyone would be no mean achievement, more like an impossibility. The government has raised expectations for leaseholders and now it must deliver.

Abolishing leasehold entirely, as has been mooted, will take years, not just political headlines. Commonhold needs to be made workable before it can replace a system embedded in millions of estate titles.

For now, landlords and investors would be wise to treat leasehold as in a long-term managed decline rather overnight abolition. They need to plan accordingly.

[Main image credit: RDNE Stock project]

Useful links:

The Leasehold Advisory Service

.avif)

.avif)

Comments