“Just because it’s legal doesn’t mean it’s right,” goes the cliché going around the news media this morning.

They’re turning somersaults in the Westminster bubble to square the circle on this one: the uncomfortable truth is that the UK’s homelessness minister had done what thousands of landlords have quietly been doing for years, simply trying to keep her rents in-line with market levels.

But it’s the way she went about it that, on the face of it at least, seems wrong.

Why tell the tenants she wanted to sell the property when clearly, as the facts seem to indicate, she had no intention of doing so. There are other ways of increasing the rent without making tenants homeless, if that’s what happened.

Ali stated in Parliament:

“…. we inherited a homelessness crisis, with record levels of people in temporary accommodation. Rough sleeping has gone up by 164% since 2010. The previous Labour Government cut homelessness and rough sleeping dramatically. We are investing to tackle the root causes of homelessness…”

If she really believes this, why behave in this way. Blatant double standards and hypocrisy on this level clearly cannot be tolerated and she’s quickly done the right thing and resigned her position.

Presumably, one root cause of homelessness is the desire (and in many cases the need) for landlords to maintain rents at market levels, especially when they have big mortgages to pay. Is it the landlord’s fault that some tenants are unable to pay market rents?

Landlords don’t operate as charities or official social housing providers, though it would seem the government would like or expect to see them doing so.

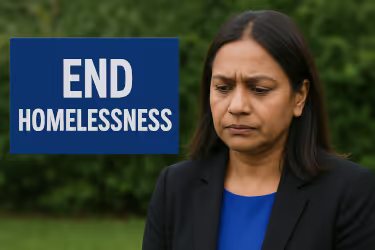

Rushanara Ali, is the Labour MP for Bethnal Green and Stepney. She stepped down from her ministerial position after it came to light that she evicted tenants from a property she owns in East London on the pretext she wanted to sell the property. She then re-let it just weeks later with a rent increase of £700 a month.

The i-newspaper broke the story last, and within hours Ali was accused of hypocrisy, bad faith, and violating the very principles behind the incoming Renters’ Rights Bill, a Labour Bill that includes measures to prevent re-letting for six months after tenants have been given notice. She told them she would put the house up for sale.

But here’s the awkward truth: what Ali did is perfectly legal. And what she did is exactly what many landlords have been doing because they can: (1) there’s overwhelming tenants demand especially in the capital and (2) it’s sometimes a far easier way than going through the Section 13 process of increasing the rent when the tenant can oppose it and may not be able to afford it.

So, the question isn’t just “should she have resigned?” It’s also: “Are landlords being held to a standard that even ministers can’t meet?” And: “How will the new Renters’ Rights Bill change all this?”

Here are some facts behind the story: In November 2024, four tenants in Ali’s East London rental property were told their fixed-term contract would not be renewed, as the home was being put up for sale. They vacated the property, presumably without objection, assuming it was to be sold. But only weeks later, they found that the same property was back on the rental market, with an advertised monthly rent increased from £3,300 to £4,000.

In her resignation letter to the Prime Minister, Ali said she had “at all times” followed “all legal requirements” and taken her responsibilities seriously. Keir Starmer accepted her resignation graciously, thanking her for her “diligent work” in housing policy.

The key issue it would seem isn’t whether Ali broke the law — she obviously didn’t. She served notice at the end of a fixed-term tenancy. She cited a property sale as the reason. Clearly, under the law as it stands landlords don’t need to give a reason to get their property back at the end of the lease term. She says she re-let the property when no sale materialised. All quite plausible and legal.

There was a request by the letting agents for the outgoing tenants to pay for some minor repairs, but Ali waived this demand. Any ordinary landlord (not in the public sphere) would have had no issues or comeback, but unfortunately for Ali she was the minister responsible for the government’s homelessness policy, a toxic mix for any MP.

The most recent data available before 2025 shows around 90 to 100 UK MPs are landlords, that’s roughly 15% of Parliament known to own rental property or declare income from property letting. The Register of Members' Financial Interests stipulates that MPs must declare rental income if it exceeds £10,000 per year.

The members across all the major parties own rentals but there’s a higher proportion among Conservatives. Some MPs declared multiple properties, and several sat on housing-related committees or voted on legislation affecting landlords and tenants.

There have been repeated calls, mainly from Labour's grassroots and Young Labour, for MPs to be barred from voting on housing legislation if they derive income from letting. The Rushanara Ali case has reignited debate on the issue, citing potential conflicts of interest between the property-owning MPs' private financial interests versus their public duties.

“How can someone charged with tackling homelessness be removing tenants and cashing in on rent hikes?” said the homelessness charity, Shelter. Jess Barnard, Chair of UK Young Labour, has said “MPs should not be landlords,” and the SNP said resignation should have been “immediate.” The court of public opinion seems to agree, the minister’s behaviour looked like profiteering rather than ethical policymaking.

The Renters’ Rights Bill embodies rules that Ali helped create. The Bill, which is due to come into force in 2026, specifically bans the very rent increase tactic Ali used. Under the new law landlords will no longer be allowed to end a tenancy on the pretext of a sale only to re-let the property at a higher rent after that.

There will no longer be any fixed-term tenancies or Section 21 evictions, tenancies will be open-ended with strict controls on large rent increases, those outside of market levels will be subject to review. Had the Bill been passed Ali’s actions would have been illegal. And that’s what brought her house down.

When the Bill does pass landlords won’t be able to claim they’re selling, then fail to sell and re-let a property for more money, or within six months. Doing so could result in enforcement action or legal claims from the displaced tenants and could result in a Rent Repayment Order. Landlords will have to provide evidence of a genuine sale and comply with any tribunal decisions on rent increases.

Rent increases will be limited to once every 12 months and governed by the strict new procedure set out in an amended Section 13 of the Housing Act 1988.

The effect of all this will be a dramatic shift in the flexibility landlords have enjoyed since the shorthold tenancy became law in 1988. Landlord flexibility will be reduced, especially in high-rent areas where small adjustments in rent can make or break viability.

One lesson from the saga is clear, transparency and ethical behaviour does matter in the end. Trust matters. Good landlords develop trust with their tenants and want to get a good reputation. If they have public roles, it’s all the more important not to misrepresent their intentions. If a landlord tells tenants she’s selling, or re-occupying the property herself, then she should do it. If she’s increasing rent, she should be honest about it and go through the proper channels.

Operating in an underhand manner, even if unintentionally, can backfire spectacularly as in Ali’s case. In a world where the power of the online review rules, every landlord is now operating in the public eye.

The Register of Members' Financial Interests says it, “contains information about any financial interest an MP has, or any benefit they receive, which someone else might reasonably consider to influence what they say or do as an MP.”

This safeguard, this level of transparency, goes to expose any conflict of interest an MP might have. The question is, amid the growing calls for MPs to be barred from being landlords, does this negatively affect their judgement and the way they vote?

The assumption is that landlord-MPs will be conflicted, and possibly compromised when dealing with legislation, shaping the rules to their own advantage perhaps? But all the evidence points the other way.

Some of the most effective housing policies have come from people who’ve actually had the practical experience of letting property, a flat, their old house, or a portfolio; they’ve had rogue tenants to deal with or tried to get a gas engineer into a property when the tenant refuses them entry.

Rushanara Ali made a major error of judgement. Was she advised to do this by the agent at arm’s length or was she directly involved? Either way it was a major political mistake. She claimed one thing and did another which smacks of dishonesty. She didn’t anticipate the blowback which as a government minister with good judgement would certainly have done.

What this episode really shows is how fragile a landlord’s reputation can be and the wisdom of dealing with tenants the right way, with consideration, ethically and within the law. In this case she should have followed the correct procedure for increasing the rent.

The Renters’ Rights Bill brings in a tougher regime when going for rent increases. Landlords will have to adapt to this, but the new rules on rent increases and reletting or reoccupying are straightforward.

Key points of the Renters’ Rights Bill - coming in 2026

Author bio: Tom Entwistle is the founder of LandlordZONE

Tags:

Comments